Tibetan Buddhism began taking shape in the 7th century during the reign of Songtsen Gampo. Two princesses – one from Nepal and one from China – are traditionally credited with bringing early Buddha images and Buddhist influence to the Tibetan plateau. Small Shakyamuni statues brought by these royal figures became focal points of devotion and helped seed the monasterial culture that evolved over the next 1,300+ years. Over centuries, Indian Buddhism, local Bon elements, and Chinese influences merged; the result is a distinct Tibetan iconography with intense ethnic and local characteristics.

How Deities Function in Tibetan Religion

In Tibetan monasteries and temples, deities serve several practical and spiritual roles:

- They are meditation supports: practitioners visualize and identify with the deity’s qualities.

- They embody specific virtues or powers: compassion, wisdom, longevity, protection.

- They form part of ritual liturgy and tantric practice.

- They offer pilgrims and laypeople a focus for devotion, offerings and petitionary prayer.

You’ll find images of these deities in nearly every monastery, temple hall and household shrine across Tibet. Knowing who is who enhances both appreciation and respectful conduct.

Buddhas

Buddhas represent awakened qualities — the perfected mind. In Tibetan temples, Buddha images are the most ubiquitous class of enshrinement.

Shakyamuni

Shakyamuni — Gautama Siddhartha — is the historical Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. Born in ancient India and enlightened around the 5th century BCE, he is the primary figure in most Buddhist canons.

Shakyamuni is often shown seated in meditation, sometimes holding an alms bowl. One classic gesture is the right hand pointing toward the earth (the “earth-touching” mudrā), symbolizing his victory over ignorance and his calling of the earth to witness his enlightenment.

In Tibet, famous Shakyamuni statues include the small childhood images enshrined centuries ago (notably those preserved in Lhasa’s Jokhang and Ramoche temples) and important large images in Tashilhunpo, Drepung and Sakya monasteries.

Shakyamuni

Other Buddhas

Commonly enshrined Buddhas also include Maitreya (Jampa), Amitābha, and Medicine Buddha. Each offers a different field of practice — future awakening, pure land devotion, and healing respectively.

Bodhisattvas

Bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who delay final Buddhahood to help all beings. In Tibetan shrines they are often displayed near or flanking the Buddha.

Guanyin (Avalokiteśvara)

Avalokiteśvara (called Guanyin in Chinese) is the embodiment of compassion. In Tibetan regions this figure holds an especially revered place — even the Potala palace is traditionally associated with Avalokiteśvara’s grace.

Representations vary: from serene single-headed forms to monumental thousand-armed versions. A frequent sign is a crown that sometimes features a tiny Amitābha Buddha, indicating Avalokiteśvara’s connection to Amitābha’s pure land.

The six-syllable mantra associated with Avalokiteśvara — commonly rendered in Tibetan practice as “Om Mani Padme Hum” — is chanted constantly by pilgrims and carved on mani stones across the plateau.

Guanyin

Manjushri

Manjushri is the bodhisattva of wisdom. In Tibetan lineages, he occupies a central place as a model of insight and learning.

Manjushri is often shown holding a flaming sword (symbolizing cutting through ignorance) and a scripture (the Perfection of Wisdom) on a lotus. His mount is a lion, representing fearless wisdom.

Manjushri

Taras (Dolma)

Tara — or Dolma in Tibetan — is a popular female bodhisattva who appears in many saved forms. She is a savior figure whose manifestations relieve obstacles and dangers.

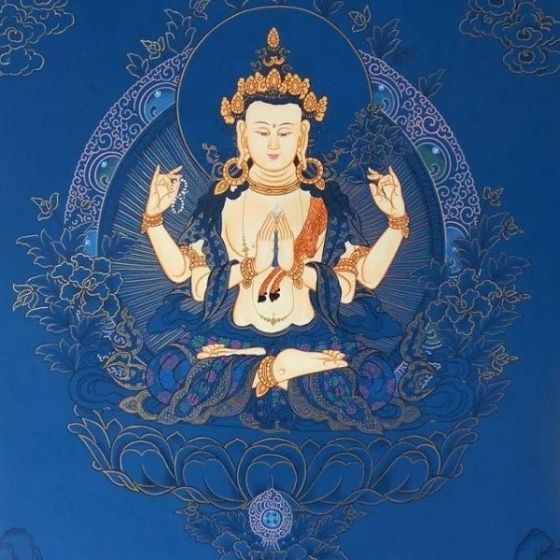

White Tara

White Tara is associated with compassion and longevity. She is frequently invoked for health and long life.

White Tara is white in color and is often depicted with seven eyes — one on her face, one on each hand and foot — symbolizing compassion’s wisdom and vigilance.

White Tara

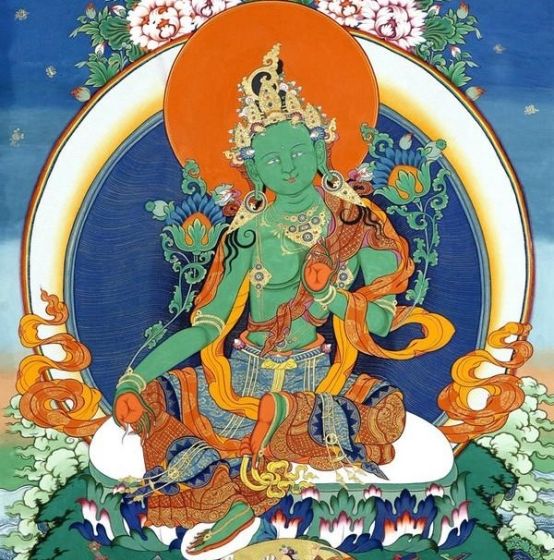

Green Tara

Green Tara embodies energetic protection and swift help. She is known as a rescuer from eight kinds of danger.

Green Tara is shown mid-movement, often with her right leg extended to step down and help others. Her left hand holds an utpala (blue lotus), and she is green in color — a sign of active compassion.

Green Tara

Goddesses and Dakinis

Female deities play vital, often fiercely protective or liberating roles in Tibetan tantric practice. They are viewed as the living source of enlightened activity.

Palden Lhamo

Palden Lhamo (sometimes equated with a wrathful form of Lakshmi) is one of Tibet’s chief protectress deities. She guards the Dharma and the ruling institutions of Tibet.

In her wrathful form she is fierce: dark blue skin, red hair, riding a mule, and wearing skull crowns. She may carry skull cups and other tantric accoutrements.

Palden Lhamo

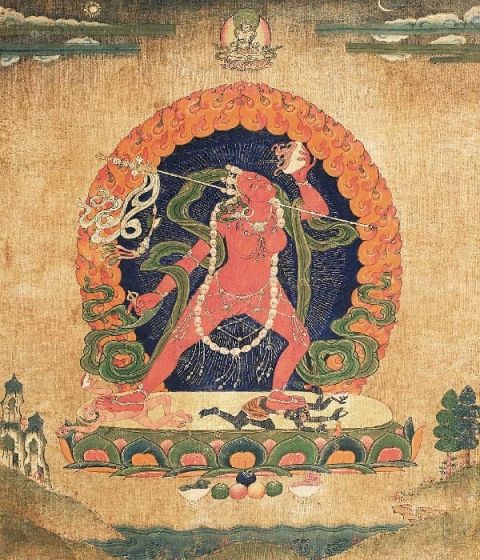

Dakini

Dakinis are sky-traveling female beings who symbolize wisdom and the dynamic, transformative energy of the practice. In Tibetan art they range from peaceful to wildly wrathful forms.

Artistically, dakinis are often shown in flying poses, sometimes partially nude, crowned with five skulls and carrying a kapala (skull-cup) and curved flaying knife — tantric symbols of transformation.

Dakini

Dharma Protectors

Dharma protectors safeguard the teachings and those who practice them. These figures are frequently wrathful in appearance — their fierce looks are meant to frighten away harmful forces.

Mahākāla

Mahākāla, literally “Great Black One,” is one of the most widely worshipped protectors across Tibetan traditions. He defends the Dharma and the monastic community.

Mahākāla is typically dark in color with multiple eyes and varying numbers of arms (two-, four- or six-armed forms are common). Wrathful flames, skulls and cremation-ground motifs often surround him.

Mahākāla

Ekajati

Ekajati is a fierce guardian especially important in the Sakya tradition and tantric lines. Devotees invoke her for protection, longevity and spiritual clarity.

She is usually dark blue with hair standing like a flame, wears skull ornaments, stands on corpses and may hold an axe and a skull cup.

Ekajati

Vajra Holders and Yidams (Tantric Deities)

In highest tantric practice, meditational deities (yidams) such as Cakrasamvara, Yamantaka, Hayagriva and Guhyasamāja appear as complex, wrathful figures — often in union with a consort — representing non-dual wisdom.

Cakrasamvara

Cakrasamvara is a central deity in many Highest Yoga Tantra practices. He embodies enlightened bliss-wisdom and the union of method and wisdom.

He is commonly depicted blue, with multiple faces and arms, embracing his consort (Vajravārāhī). His iconography is intricate — multiple faces in different colors and many ritual implements.

Cakrasamvara

Masters and Lineage Founders

Tibetan Buddhism venerates teachers whose lives shaped whole schools and practices. Their images serve as lineage links and inspiration.

Guru Padmasambhava (Padmasambhāva)

Padmasambhava, an 8th-century tantric master, is credited with establishing tantric Buddhism in Tibet and founding the Nyingma school. He is legendary for subduing local spirits and opening Tibet to Vajrayāna practices.

Padmasambhava is often shown with a fierce expression, holding a vajra and a skull-cup, wearing a distinctive hat and richly ornamented tantric attire. He often sits on a lotus and may carry a trident or longevity vase.

Guru Padmasambhava

Je Tsongkhapa

Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) founded the Gelug school and is known for his scholarship, monastic reforms and the yellow “pandit” hat associated with Gelugpa institutions.

Tsongkhapa’s statues commonly show him wearing the yellow hat and holding symbolic items: a book and a sword or the lotus and sword-and-scripture motif similar to Manjushri.

Je Tsongkhapa

How to Identify Iconography

When you stand in a temple and want to identify a figure quickly, look for these clues:

- Color: Buddhas and yidams often have specific colors (e.g., blue for Cakrasamvara, green for Green Tara).

- Number of arms/eyes/faces: More arms usually indicate tantric power and many-faced icons often symbolize multi-directional awareness.

- Attributes (what they hold): Sword = wisdom (Manjushri); bowl = compassion/renunciation (Shakyamuni); skull cup and curved knife = tantric transformation (dakinis).

- Mounts: Lions (wisdom), mules (Palden Lhamo’s wrathful travel), lotus (purity).

- Facial expression: Serene = peaceful Buddha or bodhisattva; fierce = protector or wrathful tantric deity.

Where to See These Deities in Tibet

Many monasteries and temples display canonical images. Some highlights for travelers:

- Jokhang Temple (Lhasa): Home to ancient Shakyamuni statues and a primary pilgrimage site. Expect to encounter dense devotional activity, spinning prayer wheels and packed circumambulation paths.

- Ramoche Temple (Lhasa): Another historical site with important Buddha images.

- Potala Palace (Lhasa): Associated with Avalokiteśvara and the Dalai Lamas; the palace houses significant statues and thangkas.

- Drepung, Sera, Ganden (near Lhasa): Large Gelug monasteries with rich assembly halls and protector chapels.

- Tashilhunpo Monastery (Shigatse): Seat of the Panchen Lama with major Buddha figures.

- Sakya Monastery: Famous for its unique Sakya iconographic traditions and statues.

- Samye Monastery (historic site): Associated with early Tibetan Buddhism and Padmasambhava’s era.

Always be mindful: some inner chapels may restrict photography or access, and certain statues are precious relics protected from long-distance flash photography.

Rituals, Mantras and Everyday Devotion

Deity images are more than art — they are tools for practice:

- Mantras: Short sacred phrases chanted repeatedly (e.g., Om Mani Padme Hum for Avalokiteśvara) and carved on mani stones around pilgrimage routes.

- Thangka viewing: Thangkas (scroll paintings) of deities are shown during festivals and act as mobile shrines for visualization practices.

- Offerings & Kora (circumambulation): Pilgrims walk clockwise around temples and holy mountains while spinning prayer wheels and making offerings.

- Tantric practice: Advanced meditational practices involve visualizing oneself as a deity (yidam) to transform perception.

Practical Tips for Travelers

- Dress respectfully. Modest clothing that covers shoulders and knees is best for temples. Layers are practical for altitude and weather.

- Ask before photographing. Many inner sanctums forbid photography. When allowed, avoid using flash on statues or thangkas as flash can damage pigments.

- Observe pilgrimage etiquette. Walk clockwise when joining circumambulation paths, keep voices low, and avoid pointing soles toward images or statues.

- Manage altitude. Many sacred sites are at high elevation; allow acclimatization time before exertion.

- Offerings. If you wish to make an offering, follow local customs: small bowls of tsampa, butter lamps, or incense are appropriate in many places. Always place offerings where a temple attendant indicates.

- Respect cultural sensitivities. Many Tibetan images are living symbols — treat them with reverence. If uncertain, watch local behavior and follow suit.

Common Questions Travelers Ask

Can I touch statues or thangkas?

Generally no. Touching gilded or painted surfaces can cause damage. Some pilgrimage practices do include prostrating in front of relics, but always follow local guidance and signage.

Why are some deities fierce-looking?

Wrathful forms are not evil; they symbolize fierce compassion — the energy needed to remove obstacles and cut through attachments. Wrathful iconography should be understood symbolically rather than literally.

What’s the difference between a Bodhisattva and a Buddha?

A Buddha represents complete enlightenment — the perfected state. A bodhisattva is an enlightened being who delays final nirvāṇa to help others, often symbolizing specific virtues (e.g., wisdom, compassion).

Why These Tibetan Deities Images Matter

Tibetan deities are not merely ornamental; they are living signposts to the spiritual life of a culture. Statues, thangkas and murals compress centuries of philosophy, ritual and hope into visual form. As you stand in a dimly lit assembly hall, the gaze of a thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara or the fierce stance of Mahākāla is not only art — it is an invitation to reflect on compassion, protectiveness and the possibility of inner change.

If you’d like help turning this interest into a trip, China Dragon Travel offers curated cultural tours focusing on monasteries, sacred art and authentic pilgrimage experiences across Tibet. Our guides can arrange local visits, explain iconography on-site, and ensure respectful, well-paced itineraries suited to international travelers.