Tibet’s mountains are not just geological wonders—they are living symbols of Buddhist lore, sources of Asia’s great rivers, and the world’s highest playground for mountaineering and high‑altitude trekking. With over 10,000 km of ridgelines, thousands of glaciers, and altitudes that defy imagination, each range on the Tibetan Plateau holds its own secrets.

How Tibet’s Mountains Were Born

Fifty million years ago, the relentless northward drift of the Indian Plate collided with the Eurasian landmass at speeds up to 16 cm per year. The resulting uplift created the Himalayas and elevated the central plateau by several kilometers. Even today, precise GPS measurements show Tibet rising by a few millimeters annually, reminding us that this “Roof of the World” remains a work in progress. The collision compressed sedimentary layers into fold‑thrust belts, which, over ice ages, were sculpted by massive glaciers into cirques, horns, and valleys—features still visible in every high‑altitude photograph of the region.

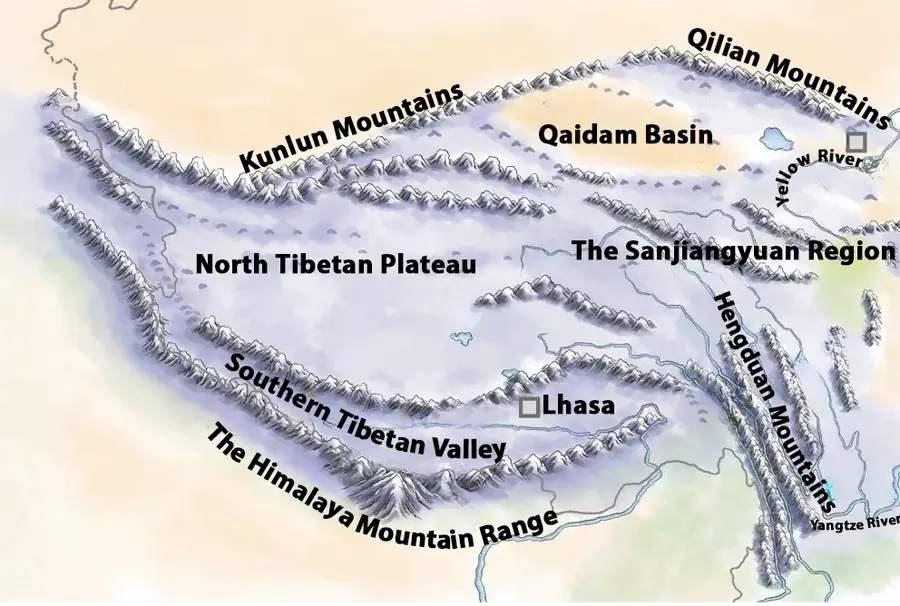

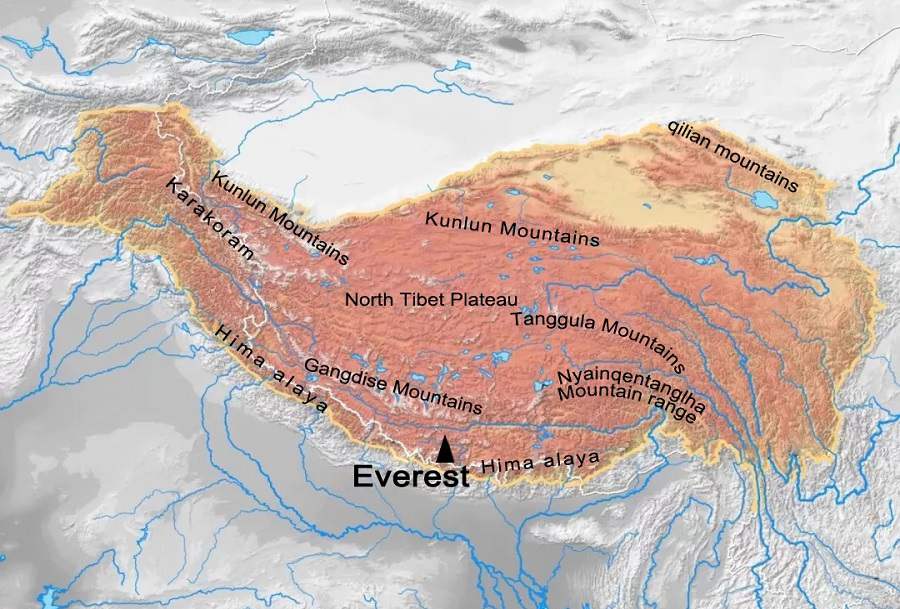

Tibet Mountains Map

The Himalayas: The Crown of High Asia

Rising along Tibet’s southern edge, the Himalayas extend 2,400 km from east to west and span 200–300 km in breadth. At an average elevation of 6,000 m, they boast more than fifty 7,000‑meter peaks and eleven giants above 8,000 m. The southern slopes, drenched in monsoon rains, support rhododendron forests and lush meadows up to 3,000 m, while the rain‑shadowed northern flanks are drier, with a higher snowline and sparse alpine steppes.

Beneath their snowy crowns, colossal contemporary glaciers—like Rongbuk on Everest’s Tibetan side—nurture turquoise lakes propped up by moraine dams. These glacial sources feed mighty rivers such as the Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) and the Indus tributaries, underscoring Tibet’s role as “Asia’s water tower.” Yet the same ice can unleash sudden floods when glacial lakes breach their natural dams, reminding visitors of both the beauty and power of this frozen world.

Mount Everest: The Ultimate Ascent

Towering at 8,848.13 m, Mount Everest (known in Tibet as Qomolangma) claims the title of Earth’s highest summit. Its pyramid-shaped summit is built of brown marble and crystalline limestone, evidence of ancient seabeds thrust skyward by tectonic might. Annual uplift of 3–13 mm continues to redefine what is “highest” even today.

Everest’s weather is notoriously fickle, buffeted by the southwest monsoon and bitter northwest winds. Temperatures can swing wildly within hours, and sudden storms can entomb climbers without warning. For trekkers aiming only for Base Camp, the gentler seasons of March through May and September through October offer the most reliable windows. Adventurers typically fly or ride the scenic Qinghai–Tibet Railway into Lhasa, then embark on a two‑day drive along the Friendship Highway to Tingri, followed by another day’s trek north to Rongbuk Monastery at 5,154 m—the gateway to Everest Base Camp.

Though popular lore speaks of two main routes, Everest actually hosts over twenty lines of ascent. Yet the Northeast Ridge via Tibet and the South Col/Southeast Ridge from Nepal dominate traffic due to their relative safety, established camps, and logistical infrastructure. Hundreds attempt these classic pathways each spring, making Everest both a testament to human daring and a tribute to the Sherpa and Tibetan communities who support every expedition.

Mount Everest

Beyond Everest: Tibet’s Other 8,000‑Meter Peaks

Just three kilometers from Everest’s summit, Lhotse rises to 8,516 m, sharing Everest’s South Col until the imposing Yellow Band. While winds are gentler than Everest’s, Lhotse endures heavier precipitation, and its north face above Tibet remains one of the last unconquered routes in the high Himalayas. In winter, temperatures can plunge to –60 °C, leaving only a narrow window for spring attempts.

A little farther west, Makalu’s dramatic, sharp ridges soar to 8,463 m. Its heavily crevassed glaciers spawn frequent avalanches, demanding technical prowess and caution from climbers. Cho Oyu, at 8,201 m, is considered the “easy” eight‑thousander, with gentler slopes that attract those seeking their first taste of extreme altitude. Shishapangma, the sole 8,000 m peak entirely within Tibet, reaches 8,012 m. Hidden from many foreign climbers by permit restrictions, its heavily glaciated flanks and icefalls test even seasoned alpinists.

Sacred Summits: The Gangdise–Nyenchen Tanggla and Mount Kailash

Central Tibet is dominated by the Gangdise–Nyenchen Tanggla Range, stretching 400 km east to west and dividing northern from southern Tibet. Among 25 peaks above 6,000 m, Mount Kailash stands out—not for its height of 6,638 m, but for its spiritual potency. Revered in Hinduism as Shiva’s abode, in Buddhism as the home of Demchok, in Jainism as Mount Ashtapada, and in the ancient Bon faith as the axis of the world, Kailash beckons pilgrims for its kora, a 52‑kilometer circuit at roughly 4,650 m that is said to erase sins and confer merit upon every turn.

Though few reach its summit—pilgrims and adventurers alike respect the mountain’s holiness—the journey itself is filled with breathtaking vistas of glacial cirques, crystalline lakes, and the serene expanse of Lake Manasarovar. Travelers often begin in Lhasa, acclimatize for two days, then follow a route through Gyantse and Shigatse, passing Yamdrok Lake’s turquoise waters and the Korala Glacier before arriving at Darchen and Manasarovar. Many choose a 15‑day Kailash and Manasarovar group tour to balance acclimatization, cultural immersion, and spiritual reflection.

Mount Kailash

The Karakoram Range: Ice Giants on the Northwest Frontier

In Tibet’s northwestern reaches, the Karakoram Range rises in stark contrast to the Himalayas. Sharing borders with Xinjiang, Tibet, and the disputed Kashmir region, this colossal spine averages 6,000 m and is home to K2 (Chhogori), the planet’s second‑highest peak at 8,611 m. The Karakoram is renowned for its massive glaciers—Baltoro, Siachen, and Biafo—which stretch for tens of kilometers and rank among the largest nonpolar ice fields on Earth.

The Great Karakoram Highway, climbing to 4,700 m at Khunjerab Pass, links Pakistan’s northern areas with China’s Xinjiang, hugging the edge of this icy realm. From Tibet, a frontier road north of Lhasa skirts the foothills, leading explorers to granite spires, glacier‑fed lakes, and the junction known as Concordia, where several 8,000 m summits dominate the skyline.

Tanggula Mountains: Birthplace of the Yangtze

At the plateau’s heart, the Tanggula Mountains form the continental watershed between Tibet and Qinghai. The range’s highest peak, Dandongfeng at 6,621 m, claims the honor as the Yangtze River’s source. From tiny springs amid rocky corries, the river gathers strength to flow over 6,300 km toward Shanghai.

The Tanggula Pass (5,072 m) is crossed by both Highway 109 and the Qinghai–Tibet Railway—the highest train route in the world. Passengers aboard the Teho (train) witness yaks grazing among ice fields and the first trickles of China’s longest river, all while traveling through oxygen‑enriched cabins that ease the strain of altitude.

Kunlun Mountains: Asia’s Spine and River Nursery

North of Tibet, the Kunlun Mountains extend 2,500 km from east to west, forming a rugged boundary with Xinjiang and stretching toward the Sichuan Basin. With summits ranging from 5,000 to over 7,000 m, peaks such as the Kunlun Goddess (7,167 m), Ulugh Muztagh (6,973 m), and Bukadaban Feng (6,860 m) pierce the sky. This range is celebrated not just for its height but for its role as birthplace of major rivers: the Karakash (Black Jade) and Yurungkash (White Jade) flow north into the Tarim Basin, while tributaries of Asia’s great rivers—Yangtze and Yellow—emerge from eastern glacial basins.

Only two major highways cross these formidable heights: 109 between Lhasa and Golmud, and 219 linking Lhatse with Yecheng. Travelers on the Tibet train marvel at desolate plateaus dotted with glacial lagoons, high‑altitude meadows, and occasional monasteries perched on windswept passes.

Hengduan Mountains: A Biodiversity Corridor and Overland Epic

In the southeast of the Tibetan Plateau, ridges and valleys of the Hengduan Mountains run north–south, creating an arc of astonishing ecological variety. From the Gaoligong Range bordering Myanmar to the Daxue Mountains crowned by Mount Namcha Barwa (7,782 m), this chain hosts temperate forests, rhododendron chapels, alpine meadows, and deep gorges carved by the Salween, Mekong, and Yangtze.

The Sichuan–Tibet Highway (G318) offers one of the world’s greatest overland drives. Beginning near Chengdu, it climbs through the butterfly‑shaped bend at Xinduqiao—where herds of yaks graze beside pine forests—descends into the rapids of the Yalong River’s “Seventy‑Two Bends,” crosses Sejila Pass at 4,728 m, skirts the turquoise surface of Basumtso Lake, and crests Mila Pass at 5,013 m before delivering travelers to the spiritual heart of Lhasa.

Comparison of Tibetan 8,000 m Peaks

| Peak | Elevation (m) | Border | Tibetan Base Camp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Everest (Qomolangma) | 8,848.13 | China–Nepal | Rongbuk Monastery (5,154 m) |

| Lhotse | 8,516 | China–Nepal | Same as Everest north approach |

| Makalu | 8,463 | China–Nepal | Shajitang Base Camp (3,600 m) |

| Cho Oyu | 8,201 | China–Nepal | Jiabula Glacier Base Camp (4,959 m) |

| Shishapangma | 8,012 | China only | North foot camp |

Seasonality: When to Travel Each Tibet Mountain Peaks

| Range | Season | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Himalayas (Everest) | Mar–May, Sep–Oct | Clear skies; manageable winds; low precipitation |

| Gangdise (Kailash) | Apr–Jun, Sep–Oct | Fewer pilgrims; temperate days; cold nights |

| Karakoram | Jul–Sep | Monsoon‑protected; peak glacier stability |

| Tanggula/Kunlun | Jun–Aug | Railway & roads fully open; lush pastures |

| Hengduan (G318) | Apr–Jun, Sep–Nov | Rhododendron bloom; autumn foliage |

Planning Your Tibetan Mountain Journey

Embarking on any of Tibet’s mountain adventures requires careful preparation. All foreign travelers must obtain a Tibet Travel Permit, and additional border permits are needed for Everest, Kailash, and other sensitive zones. Acclimatization is crucial: spend at least two nights in Lhasa (3,650 m), then ascend gradually via Shigatse (3,840 m) and Tingri (4,350 m), resting and hydrating to ward off altitude sickness.

Gear should include high‑performance layering, a down jacket, waterproof shell, insulated boots, crampon‑compatible footwear, trekking poles, and a personal first‑aid kit with Diamox or other AMS medications. Solar chargers or extra batteries are indispensable above 4,000 m, where cold quickly drains power.

Seasonally, spring (March–May) and autumn (September–October) offer the most stable weather windows across most ranges, with clear skies and manageable temperatures. Monsoon‑protected areas like Karakoram shine in midsummer, while the G318 corridor is at its most vibrant when rhododendrons bloom in late April and October’s larch forests glow golden.

About China Dragon Travel

At China Dragon Travel, we specialize in crafting seamless, safe, and soul‑enriching journeys across Tibet’s mountain realms. With over a decade of experience, our expert guides handle all permits, high‑altitude logistics, and cultural arrangements, ensuring you can focus on the wonder of every summit, glacier, and valley. From bespoke Everest Base Camp treks to sacred Kailash pilgrimages and cross‑plateau overland adventures, we tailor every itinerary to your pace, interests, and comfort. Discover the Roof of the World with us, and let Tibet’s mountains transform you.