Tibetan cuisine is a hearty, soulful reflection of life on the “Roof of the World.” Shaped by the region’s extreme altitudes, harsh climate, and Buddhist traditions, Tibetan food is more than sustenance—it’s a living culture. Every meal is designed to warm the body, fortify the spirit, and express a deep connection with the land. Whether you’re sipping butter tea in a humble yak-hair tent or feasting on momos in a bustling Lhasa teahouse, eating in Tibet is an experience woven with history, spirituality, and resilience.

Here’s your culinary guide to Tibet, one bowl of tsampa at a time.

The Core of the Cuisine: Barley, Yak, and Simplicity

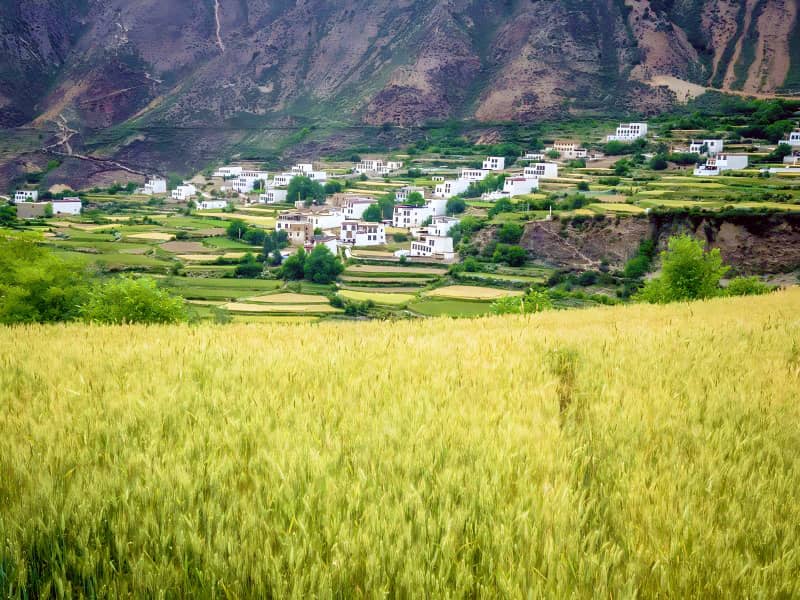

At the heart of Tibetan food lies barley, one of the few grains that thrive at over 4,000 metres above sea level. Barley is the foundation for tsampa, the most essential and emblematic dish of the Tibetan diet. Tsampa is made from roasted barley flour, mixed by hand with butter tea into a doughy ball and eaten raw. Its simplicity, portability, and energy value make it the perfect food for nomads, monks, and mountaineers alike.

Tibetan Barley

Yak is another cornerstone. A lifeline in the Himalayan terrain, the yak provides meat, milk, butter, and even wool. In Tibetan cuisine, yak meat is valued for its richness and low fat content. You’ll encounter it in stews, stir-fries, and as dried jerky during long treks.

Yak Meat

Warming the Soul: Tibetan Teas and Beverages

No Tibetan meal is complete without butter tea, known locally as po cha. A concoction of strong black tea, churned with yak butter and salt, this thick, salty drink is initially jarring to outsiders but utterly essential to locals. Butter tea isn’t just a beverage—it’s a source of calories, hydration, and warmth in a land where temperatures plunge.

Po Cha, the Butter Tea

Another popular drink is chang, a lightly alcoholic barley beer with a sour-sweet profile. Often homemade and served during festivals and social gatherings, chang is a cheerful drink that carries centuries of tradition.

Savoury Staples: From Momos to Noodle Soups

One of the most beloved Tibetan dishes among travellers is the momo—a dumpling that resembles those found across Central and East Asia but carries a distinct Tibetan flair. Typically filled with yak meat, beef, or vegetables, momos are either steamed or fried and served with a spicy dipping sauce. They are a street food staple and festival favourite, often eaten by the plateful.

Momo

Thukpa, a nourishing noodle soup, is another must-try. Made with wheat or rice noodles in a meaty or vegetarian broth, thukpa is spiced simply but fills the belly and warms the chest. In colder months or higher altitudes, it becomes more than just a meal—it’s comfort itself.

Thukpa, the Noodle Soup

Rural Specialties and Nomadic Foods

Venturing into Tibet’s rural areas opens up a world of lesser-known dishes. Sha balep, or Tibetan meat pies, are thick, pan-fried pockets of ground yak or beef with onions and spices. Crispy on the outside and juicy within, they’re perfect for a quick roadside bite.

Sha Balep

Nomadic Tibetans also prepare dresi, a ceremonial sweet rice dish cooked with ghee (clarified butter), raisins, and a sprinkle of sugar. While not part of daily fare, it’s served on special occasions and religious holidays.

Dresi

Gyurma, a Tibetan blood sausage made from yak blood and barley, is another traditional food rarely found in tourist-friendly restaurants but common in the countryside. Rich in iron and dense in flavour, it reflects Tibetans’ no-waste approach to livestock.

Gyurma

Monastic Meals and Vegetarian Options

Tibetan Buddhist monastic life has left a clear imprint on local cuisine. Many Tibetans, especially monks, eat vegetarian or avoid certain meats due to religious beliefs. Dishes like shogo khatsa (spicy potato stew), tingmo (steamed bread), and simple stir-fried vegetables offer satisfying options for vegetarians.

Shogo Khatsa, the Spicy Potato Stew

Monastic meals are typically plain but nourishing, emphasising simplicity and mindfulness. Staples like barley porridge, lentil soup, and seasonal greens cooked with butter or oil form the core of a monk’s diet.

Tingmo, the Steamed Bread

Sweet Treats and Everyday Snacks

Though not as dessert-focused as some cultures, Tibetans enjoy the occasional sweet. Khapse, deep-fried cookies shaped into elaborate knots, are eaten during New Year (Losar) celebrations. Their crisp texture and subtle sweetness make them ideal with a cup of butter tea.

Khapse

Yoghurt made from yak milk, often slightly sour and rich in fat, is another everyday indulgence. Sometimes served plain, sometimes sweetened with honey, it reflects Tibet’s long tradition of dairy craftsmanship.

Yak Milk Yoghurt

Tibetan snack culture also includes roasted barley grains, dried yak cheese (chhurpi), and hard butter candies sold in monastery shops or at roadside stalls.

Chhurpi, the Dried Yak Cheese

Where to Eat: From Teahouses to Tent Kitchens

In cities like Lhasa, Shigatse, or Gyantse, you’ll find a mix of modern restaurants and traditional teahouses, which serve up local fare alongside endless pots of butter tea. Teahouses are hubs of daily life, where people come to eat, gossip, pray, or just warm up. Expect communal seating, no menus, and simple but tasty food.

Tibetan Teahouse

In rural areas, meals are often served in tent kitchens, especially during festivals or pilgrimages. Don’t be surprised to be offered tsampa or tea by a welcoming herder—it’s customary hospitality, and refusing might be seen as impolite.

Cultural Etiquette Around Food

Tibetan hospitality is warm but observant. When offered tea or food, it’s polite to accept with both hands. Tsampa is traditionally eaten by kneading it yourself; be sure to follow your host’s rhythm. Don’t point your feet at food or religious objects, and never waste food—everything is hard-earned in this environment.

At monasteries or festivals, food may be offered as blessed sustenance, known as torma (ritual cakes). These should be accepted with gratitude and respect, even if not eaten on the spot.

A Culinary Journey Through Spirit and Survival

Tibetan cuisine may not dazzle with spice or opulence, but it leaves a lasting impression through depth, meaning, and heart. Rooted in survival and sustained by spirit, every bite tells a story of a people who have lived for centuries among the clouds. For travellers, eating in Tibet is not just about filling the stomach—it’s about tasting resilience, compassion, and community.

So come with an open mind, a strong stomach, and a respectful heart. Your journey through Tibetan food will not only nourish you—it will change the way you see sustenance itself.