Tibetan Buddhism is more than a religion; it’s a living culture woven into daily life across the Tibetan Plateau and neighboring Himalayan regions. Tibetan Buddhism grew from Indian Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions and developed into a distinct system over more than a thousand years. It blends philosophy, ritual, monastic scholarship, and intense meditation techniques. While its literature and rituals are extensive, the tradition centers on a small set of foundational ideas and practices that shape how many Tibetans see the world.

The Four Noble Truths: The Foundation

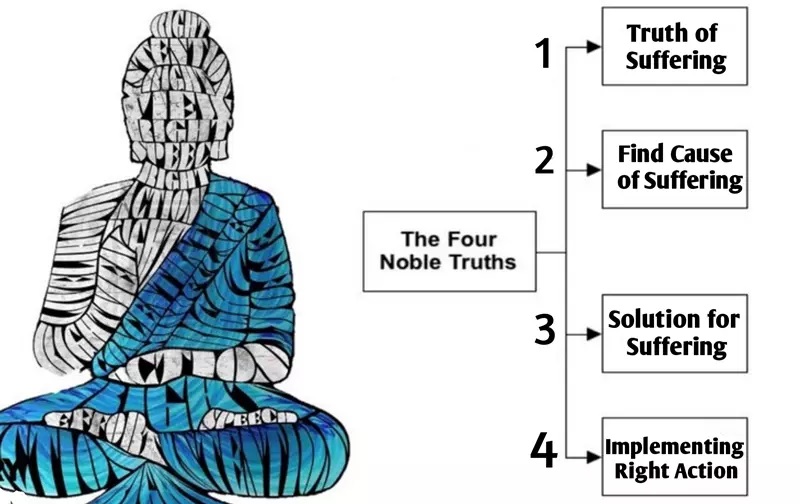

At the heart of Buddhist teaching are the Four Noble Truths — a diagnostic framework for suffering and a roadmap out of it.

Dukkha: Life’s Unsatisfactory Nature

Dukkha is often translated as suffering, but it also means instability, dissatisfaction, and the basic unsatisfactoriness of conditioned life. Birth, aging, sickness, and death all reveal how ordinary existence falls short of lasting happiness.

Samudaya: The Origin of Suffering

Samudaya identifies the roots of dukkha: craving, attachment and ignorance. These desires — for pleasure, identity, or permanence — repeatedly produce painful cycles of wanting and loss.

Nirodha: The Possibility of Cessation

Nirodha points to the possibility of ending dukkha by letting go of the cravings that cause it. This cessation is not annihilation but the awakening into freedom from compulsive patterns.

Magga: The Path That Frees

Magga is the path leading to the end of suffering — the Noble Eightfold Path — a practical set of guidelines for mind, speech, and action that fosters liberation.

The Four Noble Truths

The Noble Eightfold Path: How to Practice Liberation

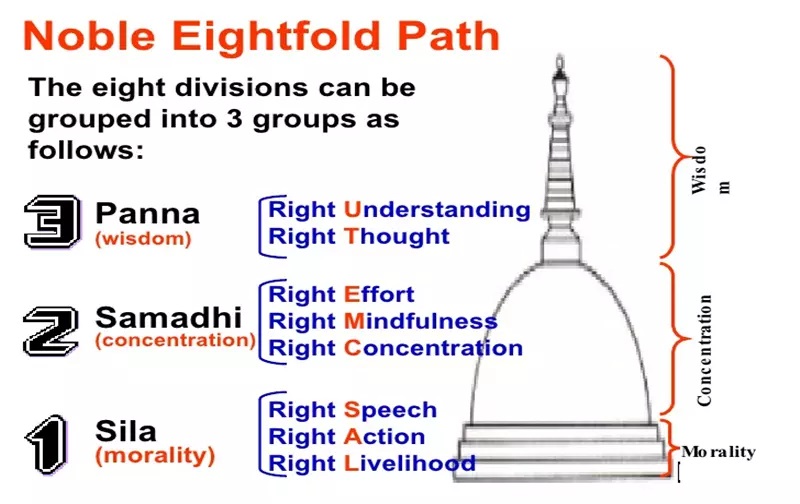

The Noble Eightfold Path is usually grouped into wisdom, ethical conduct, and mental discipline. It’s not a linear checklist, but an integrated training to transform heart and mind.

Right Understanding & Right Thought

Right Understanding is seeing life honestly — recognizing dukkha and its causes. Right Thought follows: cultivating intentions of renunciation, compassion, and harmlessness.

Right Speech, Right Action & Right Livelihood

Ethical life matters. Right Speech means truthful, helpful communication; Right Action means non-harmful conduct; Right Livelihood means choosing work that does not exploit or injure others.

Right Effort, Right Mindfulness & Right Concentration

Mental training completes the path. Right Effort cultivates wholesome states; Right Mindfulness keeps attention present (for example, breath awareness); Right Concentration develops deep stability through meditation.

The Noble Eightfold Path

Karma: Cause and Effect in Everyday Life

Karma refers to intentional actions and their consequences. It’s a moral physics: wholesome actions tend to bring beneficial results, while harmful ones tend to lead to suffering. Karma isn’t fatalism — it’s a dynamic process we influence by our choices. In Tibetan thought, karmic impressions can condition future lives until they’re fully liberated.

Reincarnation and Rebirth: Cycles of Becoming

Tibetan Buddhism affirms rebirth: beings continue through lives until awakening. “Rebirth” usually follows from karmic momentum, while “reincarnation” (as used in Tibetan contexts) can sometimes imply a conscious choice to return. Certain highly realized practitioners — known as tulkus — are believed to intentionally reappear to help others progress.

Tulku Tradition: Chosen Returns

A tulku is a recognized reincarnate teacher (for example, the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama are famous tulkus). Tulkus are traditionally identified through a mix of signs, divination, visions, and tests. Their role is to preserve and transmit teachings for the benefit of beings.

The Bodhisattva Ideal: Compassion in Action

A cornerstone of Mahayana influence is the Bodhisattva path — the vow to awaken not for personal release alone, but to help all beings. Bodhisattvas cultivate wisdom and boundless compassion, working through countless practices and lifetimes to reduce suffering everywhere.

Famous Bodhisattvas in Tibetan Practice

In Tibetan art and devotion you’ll often encounter Chenrezig (embodiment of compassion), Manjushri (wisdom), Samantabhadra (primordial virtue), and Tara (swift activity and protection). Each embodies particular virtues practitioners aspire to cultivate.

Tibetan Buddhism Bodhisattvas

Lamaism and the Role of the Lama

The term “Lamaism” historically described the Tibetan emphasis on spiritual teachers (lamas). A lama is a spiritual guide — often a monastic teacher — who embodies and instructs the Dharma. Respect for qualified teachers and the lineage they represent is central to practice, although modern Tibetan life also includes lay practitioners and diverse expressions of devotion.

Tibetan Lama

Meditation Practices: From Analysis to Deity Yoga

Meditation in Tibetan Buddhism spans analytical inquiry and focused concentration, ceremonial visualizations, and subtle completion practices.

Analytic Meditation

Analytic meditation uses reasoning and contemplative reflection to investigate the nature of self, causality, and emptiness. It’s intellectual and penetrative — not merely calming but aimed at transformative insight.

Concentrative Meditation

Concentrative practice stabilizes attention on a single object (breath, a candle flame, or an image) to build one-pointed focus and calm abiding. Strong concentration supports deeper insight.

Deity Yoga: Visualization and Non-Dual Realization

Deity yoga is core to Vajrayana practice. “Deity” here signifies a fully awakened being, not a god. Practitioners visualize themselves as the deity, recite its mantra, and train in the embodiment of enlightened qualities. The practice has two stages: generation (vivid visualization and identification) and completion (dissolving the visualization into non-dual awareness). Properly guided, it’s a skillful means to realize innate buddha-nature.

Mantras, Mandalas, and Ritual Aids

Many devotional forms accompany meditation.

Mantras

Mantras are sacred syllables or phrases repeated to focus the mind, connect with a deity’s qualities, and purify obscurations. Famous examples include the short but potent “Om” and the compassion mantra “Om Mani Padme Hum.”

Mandalas

Mandalas are symbolic diagrams representing the cosmos or a deity’s pure environment. They serve as meditational aids, mapping inner terrain and providing a sacred space for ritual and visualization.

Devotional Life: Prayer Flags, Prostrations, and Offerings

Devotional practices are visible everywhere in Tibetan regions: strings of fluttering prayer flags, stacked mani stones carved with mantras, butter-lamp offerings, circumambulation (walking around stupas or chortens), and prostrations. These acts integrate faith, intention, and habit in daily life.

Pilgrimage and Sacred Sites: Where Belief Meets Landscape

Tibetan Buddhism ties doctrine to geography. Pilgrimage circuits to monasteries, lakes, and sacred peaks form an important lived dimension of faith. Places like Lhasa’s Jokhang Temple, remote gompas (monasteries), and high lakes host rituals and seasonal festivals where locals and pilgrims gather.

What Travelers Will Encounter

Visiting Tibet or Tibetan cultural regions, expect a blend of quiet devotion and colorful ritual.

- Monasteries: Monastic life includes chanting, butter-lamp offerings, ritual music, and wall-to-wall thangka paintings and mandalas.

- Festivals: Masked cham dances, ritual dramas, and public empowerments highlight major festival days.

- Daily Rituals: Spinning prayer wheels, circumambulating stupas, and offering incense are common.

- Art & Architecture: Thangkas (painted scrolls), carved stupas, and monumental statues reveal layers of symbolism and history.

Simple Practices Travelers Can Try

If you want a small taste of practice without adopting a full spiritual routine, try these accessible exercises:

- Mindful Breathing: For five minutes, sit quietly and count the breath — a simple introduction to Right Mindfulness.

- Mantra Listening: Find a recorded chanting session or mantra and listen attentively for 10–15 minutes.

- Walk Mindfully: During a short walk, focus on the sensations of each step and the surrounding sounds.

- Observe Rituals: Attend a public prayer session at a temple and simply watch the gestures, chants, and offerings with curiosity.

Common Tibetan Buddhism Beliefs Misunderstandings Clarified

- Tibetan “Deities” are not gods in the theistic sense; they represent qualities of awakening.

- Karma is not moral punishment; it’s the tendency of intentional actions to produce consequences.

- Tulkus are not celebrities but spiritual figures recognized within a lineage.

Why Knowing These Tibetan Buddhism Beliefs Enhances Tibet Travel Experience

Understanding core teachings – suffering and liberation, compassion, and meditative skill — frames what you see on visits: the significance behind rituals, why certain sites are revered, and why people live with intentional spiritual routines. This knowledge makes visits more than sightseeing; they become opportunities to encounter a living worldview.

If you plan to visit monasteries or attend festivals, consider learning a few respectful phrases, reading about the specific traditions of the region you’ll visit, and hiring a knowledgeable local guide who can explain rituals and the stories behind sacred objects. A guide also helps navigate customs and ensures your visit supports local communities.

If you’d like to make your trip deeper and easier to arrange, China Dragon Travel specializes in culturally sensitive tours across Tibetan regions and greater Himalayan sites. We design itineraries that balance meaningful cultural encounters with comfortable logistics, recommend local guides who are fluent in English, and ensure visits are conducted respectfully so travellers and host communities both benefit. Contact China Dragon Travel for custom itineraries, festival-timed departures, or a consultation tailored to your interests and pace.