The Himalayas run in a great arc along the southern edge of the Tibetan Plateau and span multiple countries: China (Tibet), Nepal, India, Pakistan and Bhutan. The range stretches roughly 2,400 kilometres (about 1,500 miles) from its western anchor near Nanga Parbat all the way to Namcha Barwa at the sharp bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River in the east. The width from the outer Himalayan foothills to the high Tibetan Plateau varies widely – typically expressed in the range of about 200–350 kilometres. These mountains contain the planet’s highest summits and vast icefields that act as a water tower for much of Asia.

How the Himalayas Were Formed

The Himalayas are the product of an epic plate-tectonic collision. Tens of millions of years ago, the Neo-Tethys Ocean covered the land that is now the Tibetan Plateau. Around 59 million years ago, the northward-drifting Indo-Australian Plate slammed into the Eurasian Plate. The resulting compression folded, thickened and uplifted the crust, squeezing a wide tract of seabed and continental rock into towering ridges. This mountain-building event, known as the Himalayan orogeny, continues today: the Indian Plate still pushes northwards at a few centimetres per year, so parts of the range are still rising and remain geologically active.

Himalayan Climate and Topography: A Tale of Two Slopes

A defining feature of the Himalayas is their strong north–south asymmetry. The southern slopes face moist monsoon winds from the Indian Ocean and therefore receive abundant rainfall and sustain lush forests and terraced agriculture. The northern slopes, facing the Tibetan Plateau, receive far less rain and are dry, cold and high-altitude in character. This contrast produces dramatic vertical ecotones — in a short horizontal distance you can pass from subtropical hills into alpine meadows and then onto permanent snow and ice.

Why the Himalayas Matter

Beyond their dramatic scenery, the Himalayas are a climatic and hydrological engine for Asia. Glaciers and seasonal snow feed major river systems (Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra and many tributaries), supporting agriculture, hydropower and freshwater supplies for hundreds of millions of people downstream. The mountains are also a living cultural landscape — home to diverse ethnic groups, pilgrimage routes and sacred peaks.

Main Peaks of the Himalayas

This section is the heart of the article: core information about the principal Himalayan summits — their significance, location, and what travellers commonly experience around them.

Mount Everest (Qomolangma)

Mount Everest is the Himalayas’ highest peak and the highest point on Earth above sea level. Known variously as Qomolangma (Tibetan) and Sagarmāthā (Nepali), Everest dominates the central Himalayan axis. The elevation commonly cited in your source is 8,844.43 metres. Everest’s flanks host iconic trekking routes — most famously the Everest Base Camp trek (Nepal side) and approach routes from Tibet that lead to Rongbuk Monastery and the north base area. The mountain’s cultural tenor is as strong as its technical challenge: monasteries, prayer flags, and local hospitality form a powerful backdrop to high-altitude adventure.

Kanchenjunga

Kanchenjunga rises in the central Himalayas on the border between Nepal and India and has multiple high summits — it is sometimes described as a massif of “five snow treasures” because of its five principal peaks. The primary summit reaches about 8,586 metres, making it the third-highest mountain in the world. The Kanchenjunga region is remote, less crowded than some other circuits, and prized for its dramatic ridgelines, deep valleys and unique local cultures.

Lhotse

Sitting just south of Everest and linked to it on the same massif, Lhotse reaches approximately 8,516 metres. Its proximity to Everest makes the Lhotse face one of the most recognizable and formidable walls in high-altitude climbing. Trekkers heading toward Everest Base Camp will often glimpse Lhotse’s vast south face and dramatic ridges.

Makalu

Makalu stands at roughly 8,463 metres and lies southeast of Everest. It is famous for its steep ridges and pyramid-shaped summit. The mountain’s remoteness and technical difficulty make it a serious objective for experienced climbers; trekkers in nearby valleys enjoy expansive, less-touristed panoramas of this giant.

Cho Oyu

Cho Oyu, at about 8,201 metres, sits on the Tibet–Nepal border and is often considered one of the more accessible of the 8,000-metre peaks — relatively speaking — making it a popular objective for climbers building high-altitude experience. The mountain stands close to classic routes that offer sweeping vistas of the central Himalaya.

Dhaulagiri

Dhaulagiri reaches near 8,167 metres and anchors the western side of Nepal’s high range. The mountain’s name means “white mountain,” and it is known for its powerful, broad massif and dramatic north faces. Treks and routes in the Dhaulagiri area are spectacular and can be remote.

Manaslu

Manaslu, at about 8,163 metres, is another major Himalayan summit located in west-central Nepal. The Manaslu Circuit trek is famed for its dramatic passes, varied villages and the sense of remoteness it preserves despite growing popularity.

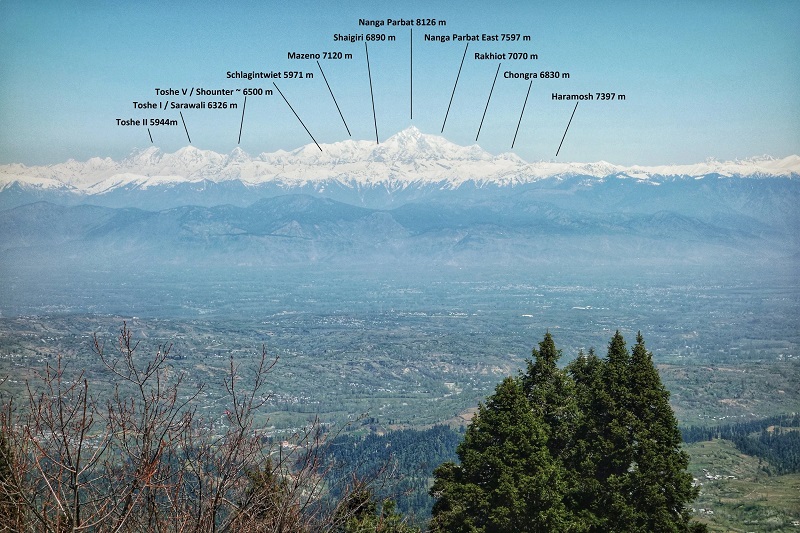

Nanga Parbat

At roughly 8,126 metres, Nanga Parbat sits at the rugged western terminus of the Himalayan arc (often associated with the western extreme where the Karakoram-Kashmir ranges meet). Famous for its imposing Rupal Face — one of the highest mountain faces on Earth — Nanga Parbat is a legendary mountaineering objective and historically one of the most challenging of the great peaks.

Annapurna

The Annapurna massif culminates around 8,091 metres and is well-known not only for its mountaineering history but for the Annapurna Circuit — one of the classic long-distance treks that crosses high passes and offers varied microclimates, from subtropical foothills to alpine heights.

Shishapangma

Shishapangma is notable for being the only eight-thousand-metre peak located entirely within Chinese (Tibetan) territory; its height is about 8,027 metres. Less visited than several other giants, Shishapangma’s eastern location and cultural context make it a unique part of the Himalayan family.

How the Himalayan Main Peaks Shape Travel and Culture

Each major peak anchors local economies, spiritual practices and trekking circuits. Villages near high mountains often host dedicated pilgrimages, seasonal festivals, and mountain-specific rituals. For example:

- Everest region: Sherpa culture, high monasteries (like Rongbuk on the Tibetan side), and a robust trekking infrastructure.

- Kanchenjunga area: Remote valleys, mixed Hindu-Buddhist traditions and high biodiversity.

- Annapurna region: Diverse microclimates and one of the world’s most famous trek circuits.

Mountains also act as sacred focal points: many summits are revered and treated with ritual respect; climbing permits and local customs often reflect that reverence.

Visiting Himalayan Mountains Regions: Practical Tips for Tourists

Planning and Permits

Access rules vary by country and region; some high valleys or border areas require special permits or restricted-area fees. Always check current permit requirements for Nepal, India, China (Tibet), Pakistan or Bhutan well in advance and work with experienced local agents to arrange logistics.

Acclimatization and Safety

High-elevation travel demands careful acclimatisation. Plan gradual ascents, include rest days, and learn the symptoms of acute mountain sickness (AMS). Even popular treks like Everest Base Camp and Annapurna Circuit require respect for altitude and weather.

Best Seasons

Generally, spring (March–May) and autumn (September–November) provide the most stable conditions for trekking and clear mountain views in much of the central Himalaya. Local microclimate differences mean conditions can vary across east–west and north–south slopes.

Respectful Travel

When visiting mountain communities and monasteries, dress modestly, ask before photographing people or ceremonies, and follow local guidance about where to walk, what to touch and how to behave during rituals.

Suggested Himalayan Peak-Focused Itineraries

- Everest Base Camp (Nepal): Classic trek with high mountain views, Sherpa culture and a strong lodge network.

- Annapurna Circuit: Long route crossing high passes with rich valley cultures and diverse ecosystems.

- Kanchenjunga Region Trek: For travellers seeking wild, less-crowded terrain and deeper cultural encounters.

- Shishapangma / Tibetan approaches: For visitors interested in less-touristed Tibetan highlands and remote monastery visits.

Final Notes for Peak-Hunters and Mountain Lovers

The Himalayan Mountains are grand, complex and alive — geologically, ecologically and culturally. The main peaks listed above are the landmark summits that define this great range and attract climbers, trekkers and pilgrims from across the globe. When you plan a Himalayan journey, balance your desire for high vistas with respect for local cultures, mountaineering safety and environmental stewardship. A Himalayan trip is more rewarding when it is slow, patient and humble before the mountains.

China Dragon Travel offers customized, culturally sensitive itineraries across Himalayan regions (Tibet, Nepal, northern India and Bhutan).