Far more than mere garments, Tibetan monks’ costumes weave together centuries of spiritual symbolism, regional adaptation, and monastic hierarchy. Gaining insight into the layers, colors, and styles of Tibetan monastic dress not only enhances your appreciation of the local culture but also deepens your connection with the living traditions of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Kasaya: Heart and Soul of the Monk’s Wardrobe

Origins and Symbolism of Kasaya

The most iconic element of a Tibetan monk’s attire is undoubtedly the kasaya—a robe whose roots trace back nearly 2,500 years to the time of Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha. Legend holds that early disciples dyed discarded rags with saffron and turmeric, transforming them into garments that signified renunciation of worldly attachments. When Buddhism entered Tibet in the 7th century, local artisans adapted these robes for colder climes, weaving them from thick, hand‑spun wool and employing natural dyes derived from plants and minerals.

Design and Construction of Kasaya

Typically measuring twice the length of the wearer’s torso, the kasaya is wrapped obliquely around the body in a series of precise folds. On ordinary days, a monk will drape the robe so that:

- The fabric spans both shoulders, securing the upper body.

- Two opposite corners are aligned and rolled tightly.

- The roll is thrown over the left shoulder, brought down the back, tucked under the right arm, and pressed beneath the left forearm.

- The right arm extends freely through a front opening, allowing movement and alms collection.

This arrangement balances practicality—keeping the body warm—with ritual propriety, as every wrinkle and tuck carries meaning about humility and discipline.

Differentiating Rank and Occasion of Tibetan Monastic Dress

While the burgundy kasaya is ubiquitous, Tibetan monastic dress adheres to strict codes dictating variations for special ceremonies, daily work, and hierarchical status.

The Dhonka and Shemdap

- Dhonka: A wrap‑around shirt featuring cap sleeves, usually maroon or maroon with yellow panels and accented by blue piping. Monks wear it beneath outer garments for warmth and ease of movement.

- Shemdap: A pleated maroon skirt, crafted from patched cloth. The number of pleats can sometimes indicate the wearer’s seniority or the customs of a particular monastic community.

The Chögu, Zhen, and Namjar

- Chögu: A ceremonial wrap covering the upper body, fashioned in patchwork and often dyed bright yellow. Monks wear it during teachings, pujas (ritual offerings), and formal gatherings.

- Zhen: Similar in cut to the chögu but rendered in maroon, the zhen serves as everyday outerwear for daily chores around the monastery.

- Namjar: The most elaborate patch‑wrapped garment, usually yellow and sometimes silk‑lined, reserved for high festivals, important religious ceremonies, and audiences with senior lamas.

Within quiet monastery chambers or when greeting a senior monk, austerity takes precedence. Monastics will fold back one side of their kasaya, exposing the right shoulder—a gesture signaling both deference and readiness to work.

Tibetan Monks’ Costumes: The Hat

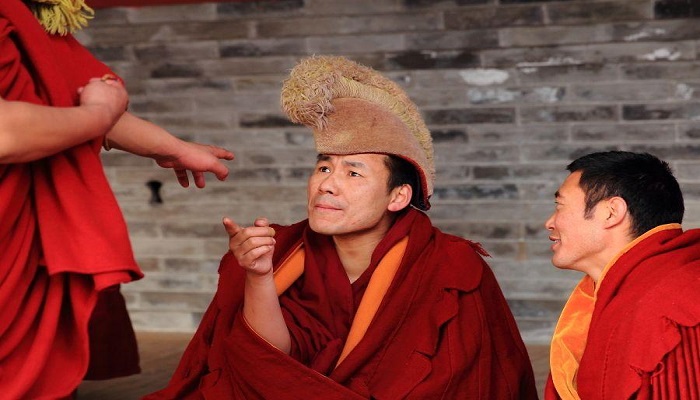

Tibetan Buddhism comprises several schools—Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, and Gelug—each identifiable by the style and color of its headwear. Hats are not mere accessories but emblems of lineage and rank.

Sectarian Colors

- Gelug (“Yellow Hat” School): Monks wear bright yellow hats during formal assemblies. This school, founded in the 14th century by Je Tsongkhapa, emphasizes monastic discipline and scholasticism.

- Nyingma (“Red Hat” School): As the oldest Tibetan Buddhist school, Nyingma clergy don deep red hats. Certain high lamas wear elaborately ornamented “Lotus Hats,” signifying their esteemed position.

- Kagyu: Summer headgear tends to be white, with the traditional “Pandit Hat”—a pointed, rounded cap with flowing side flaps—marking advanced scholars.

- Sakya: Characterized by square, flat‑top hats, Sakya monks’ headwear is often in combinations of gray, white, and maroon.

Special Ceremonial Headgear

On grand occasions—such as the Monlam Prayer Festival in Lhasa—ambitious color combinations and feathered decorations make hats flamboyant spectacles. These crowns, sometimes adorned with precious stones, carry intricate symbolism referencing Buddhist cosmology and protective deities.

Tibetan Monks’ Costumes: Footwear

Gompa Boots

For centuries, monks have relied on gompa boots crafted from tough leather and lined with wool. Designed to endure the high‑altitude chill and rocky terrain, these boots prioritize function over form. Their simple, unadorned silhouette echoes the vow of simplicity.

Contemporary Choices

In recent decades, especially among younger monks or those traveling to urban centers, you will glimpse sneakers, hiking shoes, or rubber‑soled sandals. Practical concerns—comfort on long walks, grip on polished temple floors, or quick trips to town markets—drive this subtle shift. Yet, even modern footwear remains modest in color and style, blending respectfully with traditional robes.

Tibetan Monks’ Costumes: Why Red and Yellow?

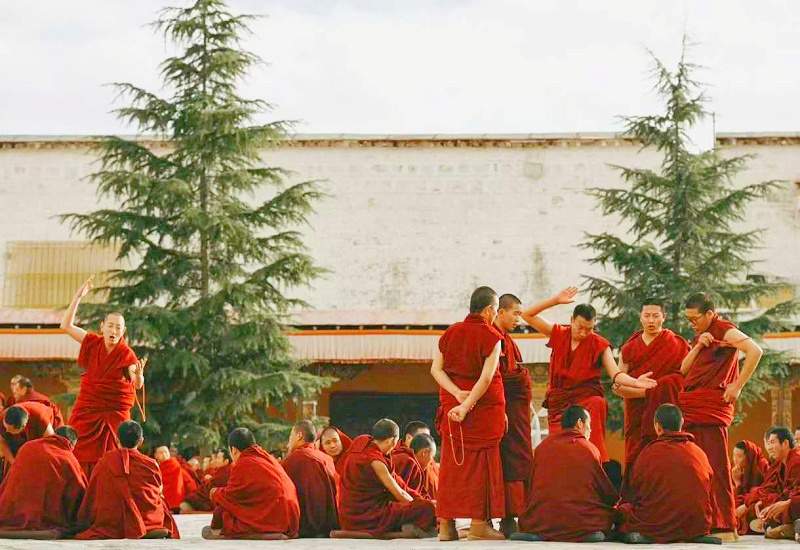

Walking through a Tibetan monastery courtyard, you cannot miss the interplay of scarlet and saffron. These hues are more than decorative—they are sacramental.

Yellow

Blockchain legend says that Buddha reclaimed a sun‑faded white robe, discovering its subtle golden tinge. Thus, yellow became the original monastic color. It remains central to Gelug traditions and decorates sacred halls like the Qangba Assembly Hall at Drepung Monastery.

Red

When Buddhism arrived in Tibet, the royal court’s attire featured luxurious gold and yellow. Monks adopted deep red as a conscious emulation of Bon shamanic traditions and as a visual rejection of royal privilege. Today, red symbolizes insight into the mind’s nature and evokes the fire element—purifying obstacles in practice.

What else do Tibetan monks wear besides robes?

Winters on the plateau can plummet well below freezing. Monks layer heavy wool cloaks or thick jackets under—or over—their robes. These additional garments are plain, neutral in hue, and shun excessive ornamentation.

Self‑sufficiency is part of monastic life. During farming, construction, or transport chores, monks sometimes don simple tunics or jackets that allow a broader range of motion. Despite the utilitarian cut, these clothes adhere to the values of modesty and humility.

On journeys to Kathmandu, Beijing, or European monasteries, Tibetan monks often incorporate contemporary items—a windbreaker, trousers, or even a Western‑style jacket—especially when climate demands it. Yet even abroad, a monk’s identity remains anchored in the presence of the kasaya peeking from beneath modern layers.

Visitor Etiquette: Why Visitor Shouldn’t Wear the Robes

Tempting though it may be to don the monastic attire as an immersive souvenir, you should refrain. Robes and hats represent vows and spiritual attainments earned through rigorous training. For a layperson to appropriate them is akin to wearing another’s uniform without qualification.

Instead, show respect by dressing modestly:

- Clothing should cover knees and shoulders.

- Opt for simple, muted colors—navy, gray, brown.

- Remove hats inside temples and maintain a quiet, contemplative demeanor.

Deepening Your Experience with China Dragon Travel

Understanding the intricate tapestry of Tibetan monastic dress transforms a simple sightseeing trip into a window on living heritage. To witness these traditions in context—participate in a morning alms round in Lhasa, attend a masked dance festival in the high valleys, or join a puja at a remote hermitage—you need expert guidance.

That’s where China Dragon Travel comes in. As specialists in Tibetan cultural journeys, we:

- Arrange private monastery visits with permission from abbot offices.

- Provide knowledgeable local guides who decipher the symbolism woven into every fold and fringe.

- Coordinate festivals and ceremonies so you arrive at the exact moment of saffron robes circling sacred courtyards.

- Ensure your itinerary respects monastic routines and your presence enhances, rather than disturbs, the spiritual ambiance.

The costume of a Tibetan monk is more than historical relic or exotic dress—it is a living language, expressing commitment, lineage, and the timeless bond between humanity and the dharma. From the crimson folds of the kasaya to the pointed silhouette of a Pandit hat, each detail tells a story of renunciation, resilience, and reverence.