Towering over vast stretches of Asia, the Tibetan Plateau stands as one of the planet’s most remarkable environments. Spanning roughly 2.5 million square kilometers at an average elevation exceeding 4,500 meters (14,800 feet), this high-altitude expanse plays a pivotal role in Earth’s climate, hydrology, and biodiversity. Its icy lakes, snow-capped peaks, and rolling grasslands create a tapestry of stark contrasts: from windswept deserts to emerald meadows, from ancient glaciers to thriving human settlements. For millennia, the plateau has drawn explorers, scientists, and spiritual seekers eager to experience its raw beauty and profound cultural heritage.

What Is the Tibetan Plateau Known As?

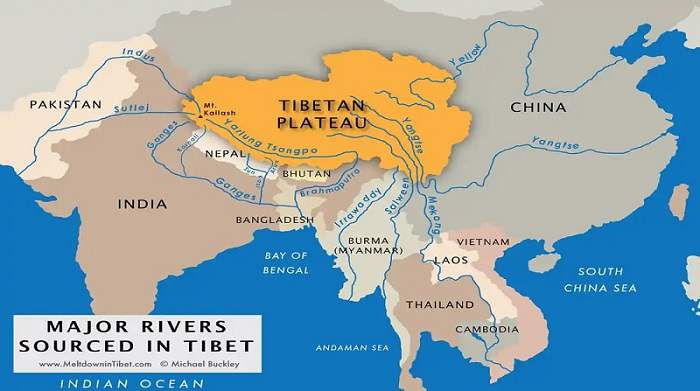

Globally recognized as the Tibetan Plateau or the Qinghai‑Tibet Plateau, this sweeping highland has earned two evocative monikers: the “Roof of the World”, for its staggering altitude and vastness, and the “Third Pole”, in recognition of its immense ice reserves – second only to Antarctica and the Arctic. Stretching across western China and into parts of India, Nepal, and Bhutan, the plateau’s elevation averages around 5,000 meters (16,404 feet), making it the highest and largest plateau on Earth. Beneath its surface lie critical water sources: glaciers and snowfields feeding Asia’s major river systems, including the Yangtze, Yellow, Indus, Brahmaputra, and Mekong. By serving as the cradle for these rivers, the Tibetan Plateau underpins the livelihoods of over a billion people downstream and exerts a powerful influence on regional and global weather patterns.

Geographic Location and Boundaries of Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau occupies the western flank of China, flanked by the soaring Himalayas to the south and west, and descending into arid deserts toward the north. To the east and southeast, the plateau meets more temperate river valleys and plains that host bustling agricultural regions. Politically, it encompasses China’s Tibet Autonomous Region, parts of Qinghai Province, and smaller portions of Sichuan, Yunnan, and Gansu provinces. Internationally, it borders Nepal and India to the south and west, Bhutan to the southeast, and India again along its southwestern edge. Its strategic position between the Eurasian and Indian tectonic plates has shaped not only its topography but also the cultural crossroads of South and Central Asia that thrive along its periphery.

Tibetan Plateau Geological Formation

The story of how the Tibetan Plateau rose to its majestic heights is written in the annals of deep time. Beginning in the Mesozoic Era and continuing through the Cenozoic, the northward drift of the Indian Plate culminated in a titanic collision with the Eurasian Plate roughly 50 million years ago. The relentless pressure forced vast swaths of crust upward, birthing the Himalayas and uplifting the hinterland to form the plateau we see today. Remnants of ancient seabeds lie buried beneath layers of sedimentary rock, evidence of primordial oceans that once lapped at what would become some of the world’s highest summits. Even now, the Indian Plate presses northward at a rate of approximately 4–6 centimeters per year, causing subtle uplift of the terrain—though concurrent erosion keeps most height changes imperceptible on human time scales.

Altitude Variations Across the Tibetan Plateau

Though celebrated for its extreme heights, the Tibetan Plateau exhibits significant variation in elevation. The northeastern fringes, where the plateau transitions to the loess plains of China, sit at elevations around 2,500 meters (8,202 feet). Moving northwest toward the Kunlun Mountains and Pamir Knot, elevations climb to 5,000–5,500 meters (16,404–18,045 feet). Towering above even these lofty regions are the Himalayan peaks along the southern margin, including Mount Everest at 8,848 meters (29,029 feet), the Earth’s highest summit. Between these extremes lie vast basins and plateaus dotted with saline and freshwater lakes, such as Nam Co and Qinghai Lake, which sit between 4,500 and 4,700 meters above sea level and offer mirror‑like reflections of surrounding snow‑capped peaks.

Climate and Seasonal Patterns of Tibetan Plateau

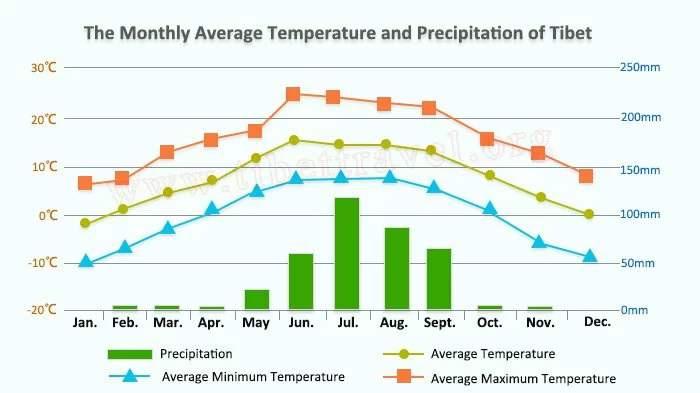

Owing to its high elevation, the Tibetan Plateau experiences a high-altitude climate characterized by thin air, strong solar radiation, and dramatic temperature swings. Four seasons can be discerned, though their manifestations differ sharply depending on region:

- Spring (April–June): As the snow begins to melt, grasslands awaken in a carpet of wildflowers. Days can be warm under the sun, but nights remain chilly.

- Summer (July–August): Influenced by the southwest monsoon, the plateau receives most of its annual precipitation during these months. Afternoon thunderstorms can roll in, replenishing rivers and nourishing alpine pastures.

- Autumn (September–October): Often regarded as the best time to visit, autumn brings clear skies, crisp air, and golden foliage in lower valleys.

- Winter (November–March): Severe cold grips the higher elevations, with temperatures plunging well below freezing. Snowfall is common in the northwest, though southern cities like Lhasa often enjoy bright, sunny days despite the chill.

Because of these extremes, acclimatization is crucial for visitors. Spring and autumn, with their milder conditions and reduced precipitation, are ideal windows for trekking, sightseeing, and cultural explorations.

Landscape Diversity of Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau is a study in topographical contrasts. In its heart lie arid basins and salt flats—harsh, windswept expanses inhospitable to most vegetation. Yet, as one traverses the plateau, landscapes shift remarkably: to rolling expanses of emerald grasslands, dotted with grazing yaks and wild antelope; to ice‑blue lakes framed by jagged mountain ridges; and to fertile valleys crisscrossed by rivers fed from glacial melts. The southeastern edge, where the plateau meets the rich biodiversity of the Hengduan Mountains, bursts with rhododendrons, magnolias, and ancient conifer forests. Moving westward toward the Transhimalaya, the terrain roughens into desolate desert reaches, punctuated by isolated monasteries clinging to rocky outcrops.

A signature way to witness this ever‑changing scenery is the Qinghai‑Tibet Railway, the highest rail route in the world. Departing from Xining, the train clambers over permafrost regions, skirting crystal lakes and pastoral grasslands before descending into Lhasa, offering travelers panoramic views that few other modes of transport can match.

Human Presence: From Denisovans to Modern Tibetans

Human habitation of the plateau is a tale of resilience in the face of extreme environments. Recent archaeological findings suggest that Denisovan hominids occupied high‑altitude sites up to 4,000 meters as early as 250,000 years ago. However, it was only around 30,000 years ago that anatomically modern humans began seasonal forays into the plateau’s fringes. Permanent settlement emerged roughly 5,000 years ago when Neolithic agriculturalists from northern China cultivated barley in sheltered valleys. Over centuries, these early settlers developed unique physiological adaptations—enhanced lung capacity, efficient oxygen utilization—that enable modern Tibetans to thrive at elevations that would leave most outsiders breathless.

Tibetan culture has been profoundly shaped by its environment. Buddhism, which took root in the 7th century CE, intertwines with local traditions, animism, and a reverence for natural features like sacred mountains and lakes. Monasteries such as Tashilhunpo in Shigatse and the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa serve as spiritual beacons, their prayer flags fluttering in the highland winds.

Cultural Highlights and Local Traditions of Tibetan Plateau

Life on the plateau revolves around a rhythm attuned to nature’s cycles. Nomadic herders track seasonal pastures with their yaks, sheep, and goats, erecting portable tents called yak wool tents that can be swiftly assembled and dismantled. In towns and cities, the sound of monks chanting, the waving of prayer wheels, and the tinkling of yak bells create a soundscape unlike any other. Festivals such as Losar (Tibetan New Year) and the Saga Dawa (celebrating the birth, enlightenment, and death of Buddha) draw pilgrims and tourists alike, transforming monasteries and village squares into vibrant centers of color, music, and ceremony.

Culinary traditions reflect the plateau’s austere environment: hearty barley flour (tsampa), yak butter tea, and dried meats provide vital calories and warmth. Handicrafts—intricately woven carpets, thangka paintings, and finely crafted jewelry—embody centuries of artistic heritage and are prized mementos for travelers.

Practical Guide: How to Reach the Tibetan Plateau

By Air

Flying is the fastest route to Lhasa, Shigatse, or Nyingchi, with direct connections from major Chinese hubs such as Chengdu, Chongqing, Xining, Beijing, and Shanghai. Upon landing at Lhasa Gonggar Airport (3,650 meters), most visitors spend the first day resting to acclimatize before exploring the city and surrounding attractions.

By Train

The Qinghai‑Tibet Railway offers a scenic alternative. Starting in Xining (altitude 2,200 meters), the route climbs across permafrost and alpine meadows to reach Lhasa over approximately 22–48 hours, depending on departure city. Special oxygen‑enriched cabins and medical assistance are available onboard to ease altitude adjustment.

By Road

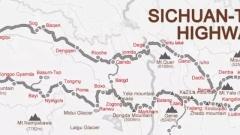

A network of highways connects the plateau to neighboring provinces. Popular overland routes include:

- Chengdu–Kangding–Lhasa: A dramatic journey through Sichuan’s gorges and Tibetan foothills.

- Qinghai–Golmud–Lhasa: Traversing the northern reaches, offering desert vistas and salt flats.

- Xinjiang–Ali–Lhasa: A rugged passage over the western plateau, favored by adventure travelers.

Regardless of mode, travelers must secure a Tibet Travel Permit through a registered agency. Independent travel without guides is restricted within the Tibet Autonomous Region, though permits are not required for other plateau areas such as Qinghai, Yunnan, and parts of Sichuan.

An Odyssey with China Dragon Travel

Exploring the Tibetan Plateau is an odyssey into one of the world’s most mesmerizing frontiers. From its geological genesis to its living cultures, from its valleys of amber barley to its peaks wreathed in eternal snows, the plateau offers a journey that is as transformative as it is unforgettable.

At China Dragon Travel, we specialize in crafting tailor‑made itineraries that immerse you in every facet of the Qinghai‑Tibet Plateau. Our expert consultants ensure seamless logistics—from securing permits and booking high‑altitude transport to arranging accommodations and guided excursions. Let us guide you on an enriching expedition to the Roof of the World, where every turn reveals a new wonder and where the spirit of adventure meets the heart of Asia. Contact China Dragon Travel today to begin your journey into the heart of Tibet.