Tibet’s identity today is inseparable from Buddhism. Monasteries, prayer flags, and spinning wheels dominate the cultural landscape, while Buddhist philosophy shapes daily life and values. But Buddhism was not native to Tibet—it traveled from India, its birthplace, across mountains and valleys, gradually taking root and blending with local traditions. Understanding how Buddhism spread to Tibet provides insight into both Tibetan culture and the broader history of Asian civilization.

Buddhism in India: The Source of Inspiration

Buddhism was founded by Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha) in the 5th–4th century BCE in northern India. Over centuries, different schools developed, including Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and later Vajrayāna (Tantric Buddhism).

It was Vajrayāna, emphasizing esoteric rituals, mantras, and meditation techniques, that became most influential in Tibet. By the 7th century CE, Tibet began to interact closely with Indian Buddhist traditions through trade, travel, and diplomacy.

The First Introduction: The Reign of Songtsen Gampo (7th Century)

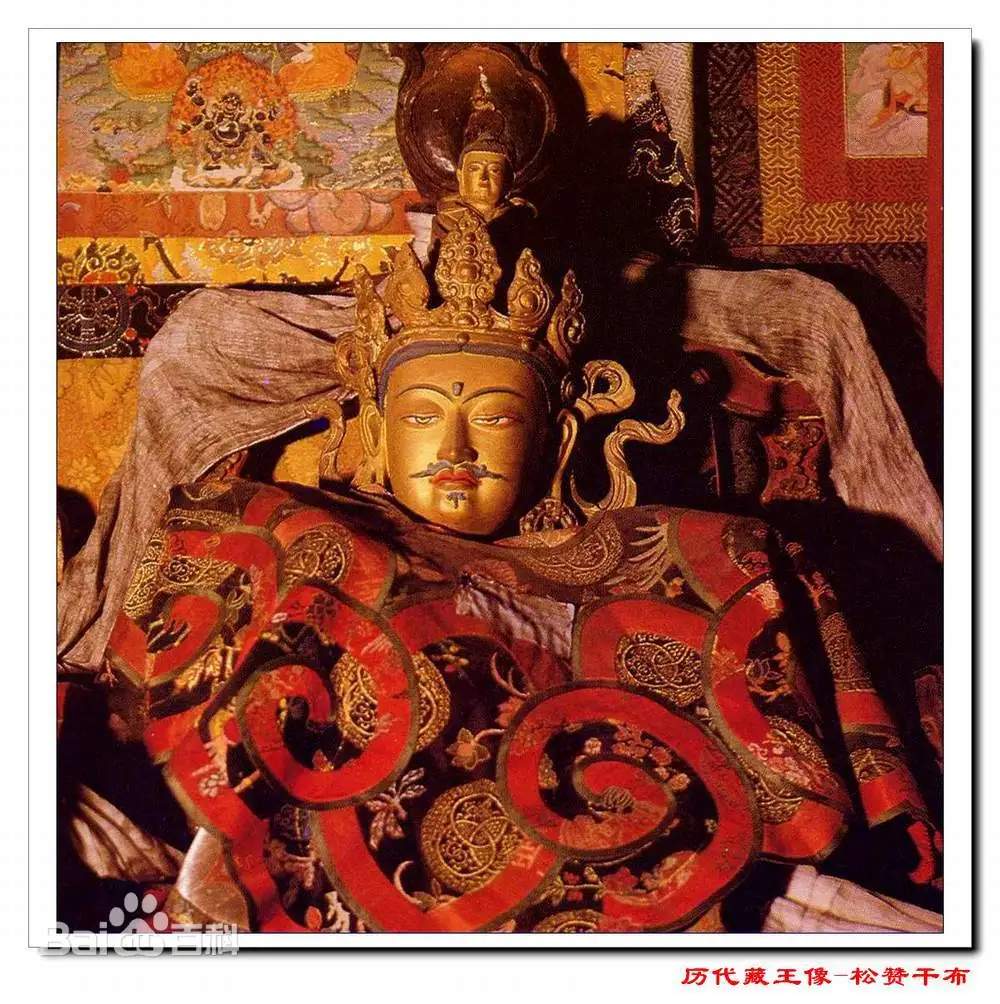

The first king credited with introducing Buddhism to Tibet was Songtsen Gampo (617–650 CE), the founder of the Tibetan Empire.

Key events:

-

He married Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal and Princess Wencheng of Tang China, both devout Buddhists who brought sacred texts and images to Tibet.

-

Under their influence, the first Buddhist temples were constructed, including the famous Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, which remains a spiritual heart of Tibet today.

Although Buddhism entered the royal court, it was not yet widespread among ordinary Tibetans, who continued to practice Bon, the indigenous shamanistic religion.

Statue of Songtsen Gampo

The Second Wave: Padmasambhava and Trisong Detsen (8th Century)

A major turning point came under King Trisong Detsen (755–797 CE), who formally invited Indian masters to Tibet.

-

Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche): An Indian tantric master who played a central role in adapting Buddhism to Tibetan culture. He subdued local spirits and integrated them into Buddhist cosmology, easing resistance from Bon practitioners.

-

Shantarakshita: An Indian abbot who helped establish monastic institutions and train the first generation of Tibetan monks.

-

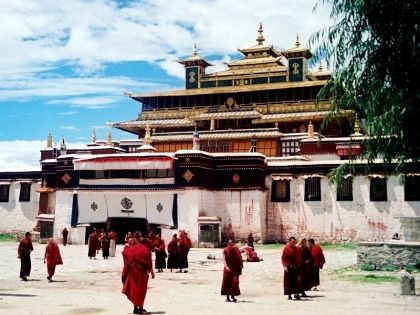

Together, they founded Samye Monastery, Tibet’s first Buddhist monastery, symbolizing the institutional birth of Buddhism in Tibet.

This period marked the beginning of Vajrayāna’s dominance in Tibet.

Challenges and Decline (9th–10th Century)

After Trisong Detsen, Buddhism faced setbacks. During the reign of King Langdarma (838–841 CE), Buddhism was persecuted and monasteries destroyed. Monastic institutions weakened, and Buddhism’s survival relied on scattered practitioners and hidden texts known as terma (treasures).

However, Buddhism never disappeared completely. Local practitioners kept the teachings alive, waiting for revival.

The Second Diffusion (Later Spread, 10th–12th Century)

From the 10th century, a new wave of transmission from India revitalized Tibetan Buddhism. This period is known as the “Later Diffusion” (phyi dar).

-

Tibetan kings in western Tibet, such as those of Guge, invited Indian masters to restore the teachings.

-

Atisha (982–1054 CE), a renowned scholar from Bengal, was especially influential. His arrival in 1042 brought systematic teachings, inspiring the development of the Kadampa school.

-

Indian scholars and Tibetan translators collaborated to translate vast numbers of Sanskrit texts into Tibetan, creating the Tengyur and Kangyur, the Tibetan Buddhist canon.

The Rise of Tibetan Buddhist Schools

During the Later Diffusion, different lineages and schools emerged, each emphasizing unique methods of practice:

-

Nyingma: The oldest school, tracing back to Padmasambhava.

-

Kagyu: Known for oral transmission and meditation practices such as Mahāmudrā.

-

Sakya: Influential in politics and scholarship during the Mongol period.

-

Gelug: Founded by Tsongkhapa in the 14th century, this school later became dominant under the leadership of the Dalai Lamas.

These traditions ensured that Buddhism was not only preserved but also uniquely Tibetan in form and practice.

Cultural Integration: Buddhism Meets Bon

Instead of erasing Bon, Buddhism gradually incorporated many of its practices, rituals, and deities. For example:

-

Indigenous mountain gods became protectors of Buddhist teachings.

-

Ritual practices such as oracles and protective charms were integrated into monastic traditions.

This cultural blending gave Tibetan Buddhism its distinct character—deeply spiritual, symbolic, and rooted in the Tibetan worldview.

Art, Literature, and Monastic Life

The spread of Buddhism transformed Tibetan culture:

-

Art: Murals, thangkas (scroll paintings), and mandalas expressed Buddhist philosophy.

-

Literature: Sanskrit texts were translated, creating one of the world’s most extensive religious canons.

-

Architecture: Monasteries like Samye, Tashilhunpo, and Drepung became centers of learning and spirituality.

-

Education: Monastic universities trained generations of monks in philosophy, debate, and meditation.

Buddhism’s Legacy in Tibet Today

By the time Buddhism was fully established, it had reshaped Tibetan society. Today, Buddhism continues to guide Tibetan identity:

-

The Dalai Lama embodies the spiritual and cultural leadership of Tibet.

-

Pilgrimage sites such as Jokhang Temple, Mount Kailash, and Samye Monastery attract devotees from around the world.

-

Tibetan Buddhism has spread globally, influencing meditation practices, mindfulness, and modern spirituality.

Samye Monastery Monks

Conclusion

Buddhism spread from India to Tibet through centuries of royal patronage, missionary teachers, translation projects, and cultural adaptation. What began as a foreign philosophy evolved into the soul of Tibet, shaping its art, politics, and daily life. The journey from Indian monasteries to the Tibetan plateau illustrates not just the transmission of ideas but also their transformation into a unique spiritual civilization.